[ad_1]

A 16-year-old employee who died after getting sucked into equipment at a Mississippi poultry plant got the job using the identity of a 32-year-old man, a new revelation that highlights the ease with which migrant children are finding work in a dangerous industry, and the challenges companies face in trying to evaluate their true ages.

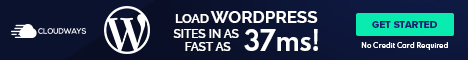

Duvan Pérez, who was hired to clean up at Mar-Jac Poultry in Hattiesburg, which supplies chicken to companies like Chick-fil-A, died on July 14. Within hours of his death, questions about his true age were raised by a local Facebook news site, and he was soon determined to be 16.

It’s illegal for minors to work in slaughterhouses, which the Occupational Safety and Health Administration considers among the most perilous workplaces in the country.

The number of children working illegally has skyrocketed across all industries, according to the Labor Department, nearly doubling since 2019. More than 800 child labor investigations in 47 states are ongoing across industries, according to the agency.

NBC News is capping a yearlong investigation into child labor in America with a new documentary called “Slaughterhouse Children,” based on reporting in two countries and six states, dozens of interviews and the review of thousands of pages of public records, accident reports and internal corporate documents.

During research for the documentary, Mar-Jac confirmed to NBC News that Perez had used the identity of a man in his 30s.

Shown a picture of the 16-year-old, Mar-Jac attorney Larry Stine said Perez did not look like a 32-year-old man. “But he might have looked 18,” said Stine, who has represented the Georgia-based company since the 1990s.

Mar-Jac blamed the hiring of the teenager on a staffing company that supplies workers to the plant.

Asked if the company was surprised to learn that Perez was 16, Stine said, “Yes, they were surprised, that I can tell you. They were surprised and somewhat horrified.”

Pérez’s family did not respond to a request for comment on his use of an adult’s identity.

Stolen identities

At least nine times in the past three years, American citizens have complained to the Hattiesburg Police Department and sometimes to Mar-Jac that their identities were stolen and being used by Mar-Jac workers, according to police reports obtained via public information requests.

One person told police in 2021 that they tried to apply for unemployment in Florida but were told their identity was being used by an employee at Mar-Jac. A police report quotes the complainant’s email saying, “I called Mar-Jac poultry to notify them and was told by [redacted], the HR supervisor that I couldn’t do anything without a police report and he couldn’t help me in any way.”

Another person called local police in 2022 saying she was unable to get child care assistance in Texas because her identity was being used by a Mar-Jac worker. “[Redacted] stated she’s never lived outside of the state of Texas,” the police report said. “She contacted HR at Mar-Jac and was informed that they couldn’t give her any information and to contact the police department.”

Mar-Jac said it has reviewed its entire workforce and does not believe that it is employing anyone under 18. Stine said the company is limited in how much scrutiny it can apply to the documentation beyond the government’s E-Verify system: “Under the way the rules are set up, we’re limited. They gave us this documentation, we cannot look into it.”

The Labor Department maintains that it is up to the companies to conduct due diligence when hiring workers to determine if they are legally old enough to do the job.

After Pérez’s death, the Labor Department launched an investigation into how Mar-Jac hired a teenager and a separate OSHA investigation into the accident itself. Both investigations remain ongoing.

In September, OSHA appealed to Mar-Jac employees in a press release to reach out to the agency to discuss the circumstances around Pérez’s death, noting that federal law protects the rights of workers to participate in a Labor Department investigation.

The Department of Homeland Security is supporting the OSHA investigation, according to a DHS spokesperson. Stine said, “Mar-Jac is unaware of any involvement by DHS.”

In an email, Stine said, “Mar-Jac thoroughly investigated the accident and has not found any errors committed by its safety or human resources employees. It has learned many lessons from the accident and has taken aggressive steps to prevent the occurrence of another accident or hiring underage workers.”

If a company is found to have violated child labor laws, the maximum fine is $15,138 per instance.

Asked if the potential fines affect how a company does business, Stine said, “I think the publicity of having something like that is far worse than the penalty. Nobody wants to be seen to have been hiring a child.”

Pérez was the second person to die after getting entangled in equipment at the plant in the past two years.

Laura Strickler / NBC News

Pérez’s uncle Gildardo Pérez told Telemundo he was unaware of the risks of the job and might have spoken up if he had known. “Perhaps we would have prevented it, but we never knew if it was a dangerous job.”

A representative for Chick-fil-A, which buys chicken from Mar-Jac, said in a statement, “We are reviewing our own procedures for investigation and response as we pursue the steps necessary to effectively hold all our suppliers to our high safety standards.”

A Mar-Jac worker who said they work legally for the company and asked to remain anonymous out of fear of losing their job said representatives of Chick-fil-A come and visit the plant. “Supervisors advise us to please do the work well because the bosses from Chick-fil-A will pass through to check the work,” the worker said.

Plant employees also receive a coupon for a free Chick-fil-A sandwich once a year, the worker said.

‘A massive flow of boys and girls’

In a year of reporting, almost all of the examples of child workers found at meat-processing plants across the country have come from Guatemala.

During the past two years, more than 250,000 unaccompanied children have come to the U.S. Almost half of those minors are from Guatemala.

Many of these children come from rural, Indigenous towns where the human smuggler, known as a “coyote,” is often a community member, experts say, and families commit to paying back thousands of dollars in order to get to the U.S.

Some of those children have found job openings at slaughterhouses across the country. Some look young but are over 18. Other workers, seen in pictures taken by Labor Department investigators, clearly appear to be children.

Duvan Pérez was from a small mountain village called Huispache in western Guatemala near the Mexican border.

NBC News and Telemundo went to Huispache to learn more about the factors that push young people to leave the country. The migration of children, including many traveling alone without their parents, is having an impact.

Data obtained from Guatemala’s Ministry of Education shows that more than 1,500 schools have closed in Guatemala in the past 15 years.

The Ministry of Education has not responded to requests for comment as to why the closures are happening, but one Guatemalan government agency notes the demand for education is decreasing in part because kids are leaving for the U.S.

Estuardo Sánchez, who works with UNICEF in Guatemala, said the exodus of children in recent years is significant. “It’s a massive flow of boys and girls who are leaving the country,” he said. “Guatemala is losing its good demographic, that human resource, because the kids who leave are the bravest, the entrepreneurs.”

Labor Department crackdown

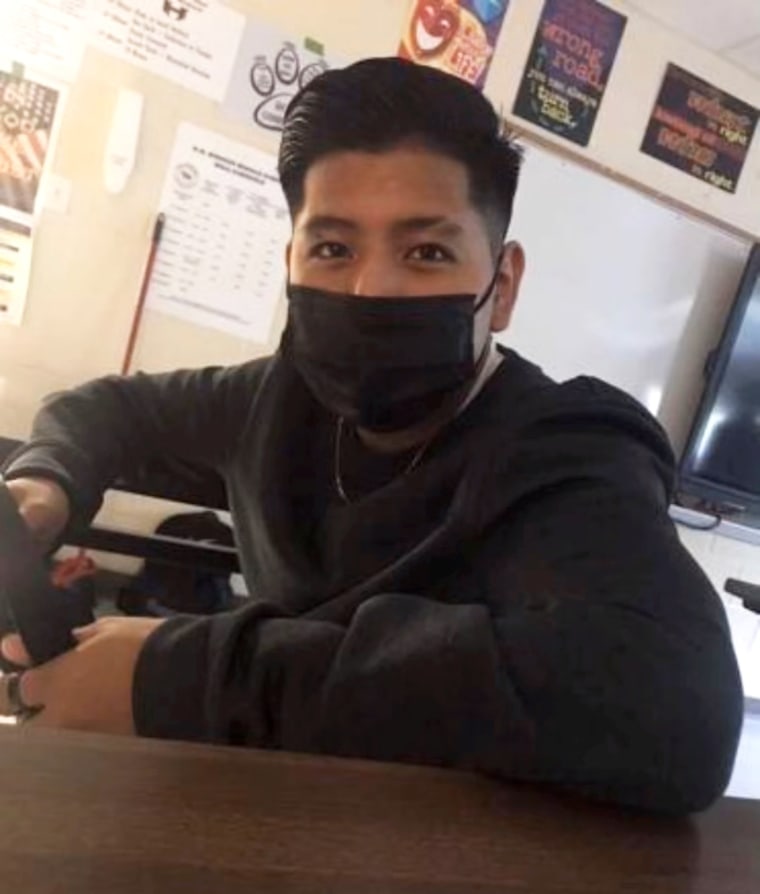

Child labor in the U.S. first emerged as a fresh concern in late fall 2022 when the Labor Department announced it had found more than 30 kids illegally working the graveyard shift for a company that cleans the biggest slaughterhouses in America, Packers Sanitation Services Inc.

Ultimately the Labor Department found 102 children working for PSSI at 13 locations in eight states.

PSSI paid a $1.5 million civil penalty and agreed to third-party monitoring. The company maintains it did not knowingly hire children. It said the only way minors could have been hired is if they used stolen or fake identities to get the jobs.

The company also said it has a strong commitment to a zero-tolerance policy against employing anyone under the age of 18 and it has since “implemented enhanced screening processes and technologies” in its hiring practices.

Since the settlement with the federal government, PSSI has also installed a new CEO and hired its first-ever compliance officer.

Since the allegations against PSSI came to light, other companies have also come under scrutiny.

Tyson Foods, Perdue Farms, Hearthside Food Solutions and Gerber’s Poultry in Ohio are also now under investigation by the Labor Department after it was alleged that children were working inside their facilities. The companies have said in separate statements that they are cooperating with Labor Department and have strict policies against hiring anyone under 18.

Tyson Foods wrote in a letter to senators who were investigating child labor: “Tyson Foods is committed to compliance with all labor laws and holding those we do business with to the highest standards of accountability.”

Perdue Farms said in a public statement: “Underage labor has no place in our business. We are appalled by these recent allegations as they are not representative of who we are as a company and what we stand for.”

A spokesperson for Hearthside Food Solutions pointed to an editorial by the company following an investigation by The New York Times that said in part: “When we became aware of the story, we took decisive action focused on rooting out what may have enabled underage workers hired by our staffing agencies to enter our facilities.”

NBC News broke the story that FBI agents found more than two dozen minors working at the Gerber’s Poultry plant in a midnight raid in October. The company said that it is cooperating with federal authorities, adding: “We have formal identity verification procedures in place and dedicate significant resources to ensure that Gerber’s Poultry employees and contractors are legally authorized to work.”

What federal investigators can’t do is recover the months and years that migrant minors have spent on the job. Pastor Joel Tuchez of Dodge City, Kansas, said the kids he’s met through his ministry who’ve worked in the meatpacking plants of Kansas were robbed of their childhoods. “You have to act like an adult. You have to behave like an adult. You have to perform like an adult. And if you mess up, you get treated like an adult.”

FARRATA NEWS Online News Portal

FARRATA NEWS Online News Portal